Jeddah Architectural Guide | CP/07

مبنى مقر شركة رجب وسلسلة |

|

Rajab & Silsilah HQ office building CP/07 |

|

| CORPORATE BUILDINGS/07 | |

| 1980 | Studio Sessanta5 |

| 34 m | 7 Floors |

| 4,375 m2 | 1,830 m2 (Site) approx. |

As the name suggests, the “Studio Sessanta5” (pronounced Sessanta Chinqwe) was formed in Turin, Italy in 1965. It was originally formed as a group of young painters and students from the faculty of Architecture at the University of Turin. The group consisted of five members; Franco Audrito, Enzo Bertone, Paolo Morello, Paolo Rondelli, and Roberta Garosci, all of whom (as students) worked for the editorial staff of the Turin-based magazine “Classe operaia” (Working Class), which has just been founded by Italian literary critic, historian, and politician Alberto Asor Rosa.

The magazine’s original activities were of an explicitly political nature, reflecting the growing activism of students in Europe and elsewhere in the Western world, dealing with the emerging issue of the relation between knowledge and practice-with relevance to the architecture practice as well- in a world in need of transformation through a class war.

The studio was at the forefront of a burgeoning ideology that characterized the period, not only in Italy but across Western Europe: a growing disillusionment with and criticism of the Modern Movement.

This era saw a surge of young Italian architects seeking to revolutionize the field by rejecting its recent influences. They challenged the established “masters,” embracing a future-focused approach that viewed the past with skepticism and the future as a canvas for continuous innovation. This was a period where many young Italian architects attempted to radically break away from architecture’s most recent “mold. During that period, the “past” was seen as obsolete, while the future offered endless possibilities for experimentation.

Certainly “experimentation” was the most apt descriptor for that volatile period where generations clashed not only in the sphere of architecture but as is well documented, in almost all aspects of cultural expressions and political manifestations.

However, as events started to calm, it is worth noting, according to Audrito’s own writing, their growing inspiration and interest at the time in the works of the American architect Louis Kahn. As the author Maurizio Vitta explains in his introduction to the works of “Studio Sessanta5” published by L’Arca in 1995: “Kahn was essentially interested in the deepest foundations of society, valid everywhere and at all times; and it is on this basis that he devised a design model constructed out of simple geometric forms, in whose composition he set out to express the historical reason of collective archetypes rather than the type of industrial reason associated with the Bauhaus theories.”

Louis Kahn’s work resonated with young architects in the 1960s due to its reflection of societal tensions and innovative reinterpretation of Western design conventions. His ideas offered a response to the desire for change, proposed a new, practical design approach, and, most importantly, demonstrated the potential for a global architecture that could contribute to a more equitable society, or what Vitta continuously refers to as “a sort of inverted exoticism”.

It is within this context, and after a period of more extreme “experimentation’ during the 1970s that the construction boom in Saudi Arabia came calling to many architecture practices in Europe, where Italian firms had a head start due to the involvement of several engineering consultancies way back since the 1960s when Saudi Arabia embarked on a massive infrastructure and roads upgrade and expansions across the country. It is worth noting the role of the Italian firm Italconsult and the vast number of civil and infrastructure projects it has worked on across the Kingdom.

It was an interesting period for Italian architects, a period that Maurizio Vitta highlights as that when Italian architecture “has mainly blossomed outside Italy,…”. Architects such as Rome based Studio Valle have already been quite active in the region, especially in Jeddah.

The first period of “Studio Sessanta5” work in Saudi Arabia stretched from 1976 to 1985. During this period the studio designed a vast array of building typologies, from private villas to office buildings to the occasional institutional buildings.

The studio approached their work with a flexible and determined mindset, recognizing the importance of adapting to the local context. They demonstrated humility in their methods and ambition in their goals. This sensitivity to the task at hand led to a thoughtful integration of their modern architectural style with local traditions. As a result, their designs incorporated symmetrical, rectangular forms to convey modernity, while also drawing inspiration from local historical references to create, what they perceived to be, a unique juxtaposition of contemporary architecture with “assumed” traditional values.

One of these buildings was the Rajab & Silsilah office Buildings, also known as the Philips showroom building since the company was the sole agent of Philips electric consumer goods in Saudi Arabia. The office building is located on the prominent Palestine Road, opposite the Solaiman Fakeeh Hospital complex, and not too far from the American Consulate complex and compound in Jeddah, which occupied the corner location for more than thirty years (the American Consulate has recently been relocated to a northern suburb of Jeddah, however, the grounds still remain guarded and is still probably diplomatic property.)

Similar to many merchant families of Jeddah during this period, whose recent thriving business has been impacted by the Oil and construction boom witnessed in Saudi Arabia during the period between 1970 – 1986, the Rajab & Silsilah group embarked on building their own business HQ to cater for their growing business activity and to announce their presence as part of the expanding urban development of the city of Jeddah during that time. An intense period of construction, where many prominent landmarks in Jeddah were built. Examples such as the Queen’s Building on King Abdulaziz Road in Balad and Adham Centre on Madinah Road were all built during this time. Naturally, all these office buildings were located on prominent commercial roads, and have come to constitute a significant component of the identity of the modern evolution of the coastal city.

The Rajab & Silsilah office building was finished in 1980, and it is an expression of the construction material, mainly composed of reinforced concrete cylindrical volumes that rise up from the narrow site. This constrained location, amongst mostly low-rise residential and local retail outlets, has probably dictated the congested massing of predominantly monolithic vertical volumes that appear to have been bundled into an office building. Openings and windows have been kept to a minimum and are always deeply embedded between the volumes’ cavities and resultant spaces. This has probably minimised the impact of direct and often glaring sunlight into the office spaces, while at the same time, has given the white-washed concrete volumes their sculptural appearance. One cannot but help notice how the architecture would have been an appropriate nod to the efforts by the Architect Mayor of the time; Mohammad Said Farsi, to introduce sculpture and art to the public realm in the ever-expanding city of Jeddah.

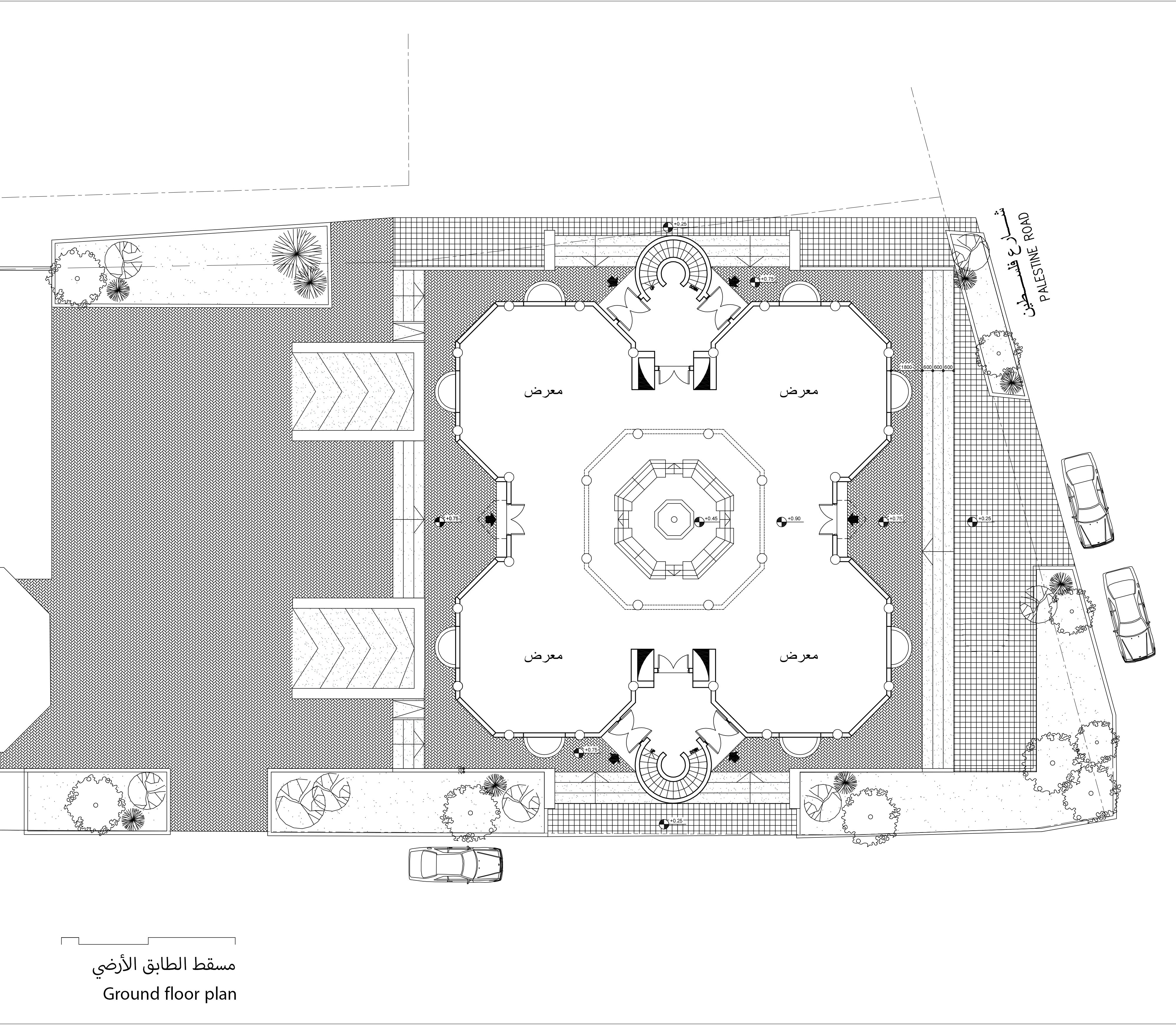

The ground floor is mainly composed of showroom spaces with shop display façade facing the main road. Due to the site constraints and narrow proportions of the site, the entrances to the office building lobby and access to the upper floors has been shifted to the side roads, where the cylindrical volume of the main staircase and building cores are located. There is no room for a grand entrance to the office building, and staff normally make their way to the upper floors via a seemingly side door that could be easily mistaken for an emergency access door.

Another nod to the Jeddah location is the use of vivid sky-blue window profiles that are clearly inspired by some of the traditional houses in the Balad area of Jeddah’s historic district.

Drawings & photography by urbanphenomena ©

References:

-

Audrito, Franco. (1995). Lo Studio65: architettura e design. Arcaedizioni.